About Hoyle Mill in Thurlstone

Our History

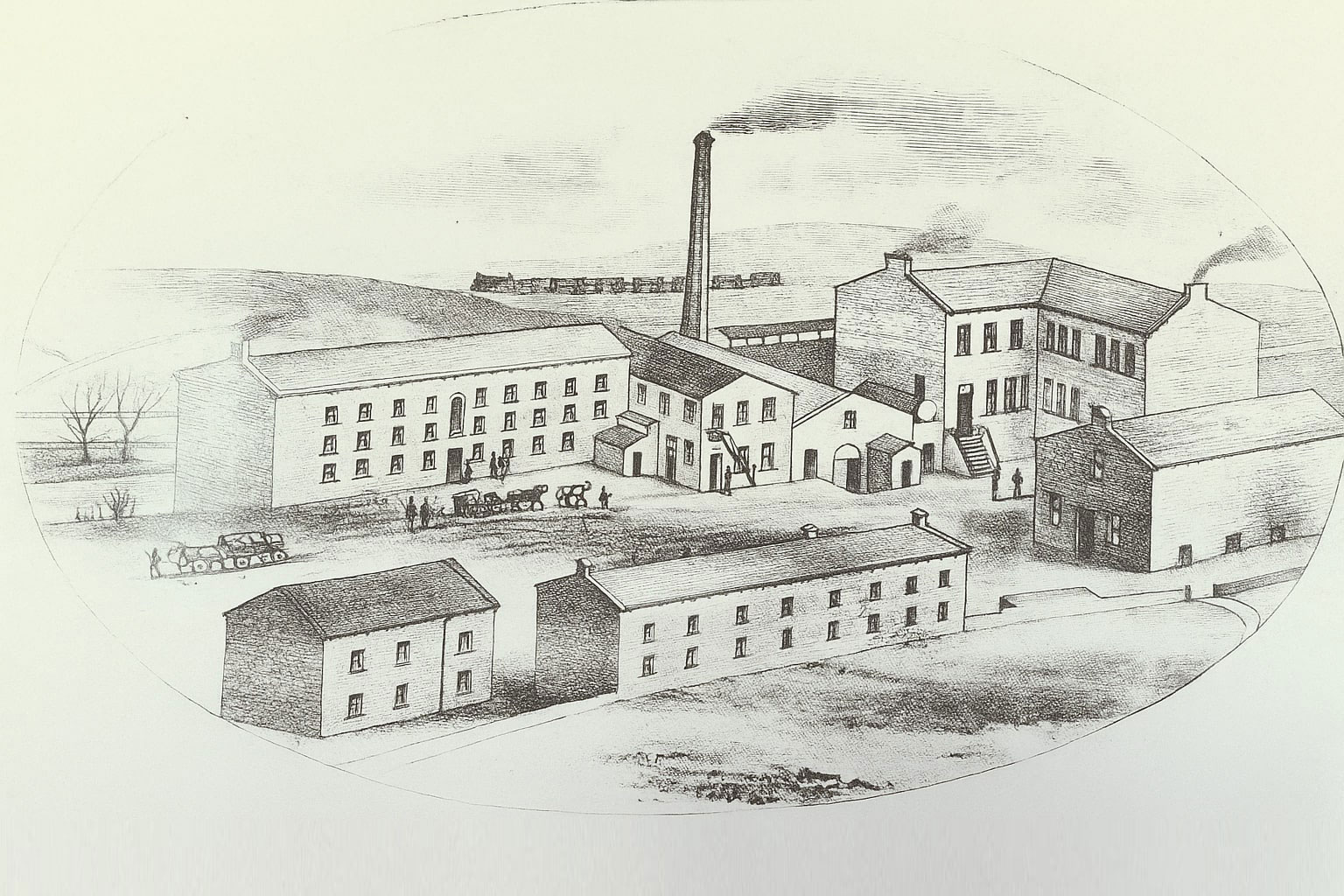

From its early days as the Oil Mill to its later life as Hoyle Mill, this site has been at the heart of Thurlstone’s heritage. Every stone and waterwheel tells a story of the people, work, and community that shaped it.

Origins of the Oil Mill

The Oil Mill at Thurlstone was established in 1740 by James Walton, son of James Walton (1672–1729), a salter. Alongside the mill, the younger James also built Thurlstone House.

In 1764, a dispute arose between John and James Walton and Aymor Rich, owner of Hornthwaite Corn Mill. A weir built to power the Oil Mill was said to obstruct the river, causing Rich’s mill to stand idle at times which incured a loss of up to six shillings a day. The matter was eventually settled out of court.

The Milner Family and the Mill

The last Walton connected with Thurlstone, Susannah, married Gamaliel Milner of Attercliffe Hall. She inherited her grandfather’s estate but never lived at Thurlstone herself. Susannah’s son, Gamaliel Milner, was the first of the Milner family to live at Thurlstone and is believed to have worked the Oil Mill. His younger son, John Crossland Milner, later managed it, while his elder brother pursued a legal career. The mill became known for producing “hair line cloth” which was a striped grey-and-black fabric widely used for trousers.

When John Crossland Milner retired in 1872, management passed to Mr. James Studley Nokes, as John’s son Gamaliel had entered the Church. The mill was later rented to Benjamin Whiteley, who specialised in sheepskin rugs. After Whiteley built his own mill at Bridge End in the early 20th century, the Oil Mill stood empty for a time before being occupied by Messrs Hogley and eventually sold to Messrs Hoyland.

In 1861, a fire broke out at the mill and shots were fired through the windows of Thurlstone House which were possibly linked to unrest in the Chartist period.

Life at the mill

The Oil Mill originally stood just below the weir, powered by a large waterwheel. A high footbridge once crossed the weir and the mill itself also kept a giant wooden rattle which served as a fire alarm for the night watchman.

At one stage, the mill was owned by John and Benjamin Wainwright, linseed oil manufacturers. Linseed oil was in demand for paints and inks, and even for the red dye used to cancel the first postage stamps, such as the Penny Black. The residue from seed crushing was pressed into “cattle cake,” an important feed for fattening livestock during the agricultural and industrial expansion of the 18th and 19th centuries.

Later Years and Legacy

In its later years, the site operated as a woollen mill, and for a time a Sunday School for Church of England children was held in an upper room until a dedicated day school was established in Thurlstone.

Like many riverside industries, the Oil Mill was noisy and carried strong smells, from linseed oil to the processes of fulling and wool production. Yet for generations, it played a vital role in the life of Thurlstone. Though now long gone, its story remains an important part of the area’s heritage.